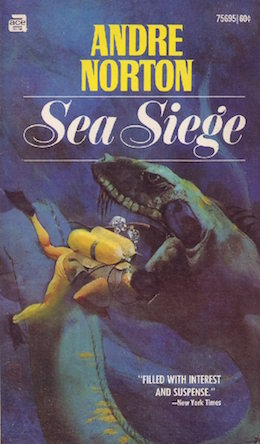

For the first time in my reading and rereading of Andre Norton’s novels, I’ve found one that happens during the atomic holocaust. Especially in the Fifties, she referred to it constantly, taking as a given that Earth would nuke itself. But her stories nearly always take place in the aftermath, sometimes very long after—Plague Ship, for example, or Daybreak/Star Man’s Son.

In Sea Siege, the big blow comes midway in the book.

It’s pretty clear it’s coming. Protagonist Griff Gunston (could there be a more perfect Fifties boy’s-adventure name?) is living a boy’s dream on Caribbean island with his scientist father and his father’s assistant, Hughes. He swims, dives, and hangs with the native inhabitants of this bleak expanse of rock and salt. He’s aware that the outside world is lurching toward war, and there are signs that all is not well with the environment. Boats are disappearing, colonies of mutant octopus are proliferating, and an actual sea serpent shows up dead on the beach. At least part of the world is radioactive already, and it looks as if the great powers—the US and the “Reds”—are set to finish the job.

The US military, in the form of a unit of Seabees, takes over a section of the island and rapidly gets to work building a base called, literally, “Base Hush-Hush.” The base commander is a sensible sort but his security officer is a martinet. The scientists at first come into conflict with the base, as it tries to cut them off from areas important to their research. Fairly soon however they form an uneasy alliance with the sailors to investigate the changes in the sea life, notably the big octopus colony that’s rumored to exist. These creatures seemed to have evolved higher intelligence, and there’s no common ground with humans.

While the Americans work out their differences, the islanders have their own issues. They’re a mix of various colonial and enslaved peoples, with active beliefs in voodoo. One of their leaders, Dobrey Le Marr, is friendly to the scientists, but he doesn’t pretend to be able to control his people, who are superstitious and sometimes violent about it. They believe the Americans have brought bad luck and contributed to the disappearance of their ships. They’re not particularly happy about the destruction of the planet, either, as represented by their own, already badly damaged portion of it.

In the midst of demonstrating what the scientists do, Griff and company are called to help rescue a missing diver from the base. They find the lair of another sea monster, and Griff’s father is also lost. Griff finds him after a harrowing subterranean search (Norton loves her underground terrors); he’s badly injured, and barely makes it back to the base.

The injury turns out to be caused by a creature that should not even be in this part of the world: a scorpion fish, and apparently a mutant variety. The only way to save Dr. Gunston’s life is to airlift him back to the US—right on the verge of nuclear war.

He’s barely gone (and pretty rapidly forgotten by everyone including his son) before it all comes down. Word comes through on the radio that major coastal cities all over the world have dropped off the radar, from Sydney to Seattle to Cape Town. Meanwhile the islanders take out their fear and anger on the scientists’ installation, leaving Griff and Hughes homeless. They hole up with the Commissioner of the island, helping man the radio in hopes of getting news from the outside world.

Then the sea turns actively hostile. Something is driving masses of maddened sea life toward the island. On the heels of that comes the storm: a mighty wind and a volcanic eruption that just about tears the island apart. Something rides it: sea serpents controlled by giant intelligent octopuses. There’s war on multiple fronts, not just the nuclear holocaust but the earth and the ocean itself rising up against humans.

After the storm, the survivors band together and pool their resources. Griff comes across a familiar face as he explores the altered landscape: the lab’s cleaning lady, Liz, who is a voodoo priestess, and who has dug in with a family in a pocket of livable, arable land. Liz is the first functional human female I’ve seen in months of rereads, and she’s tough and smart.

But the weather isn’t done with the island and its inhabitants, and a massive hurricanelike storm batters the island for days. Griff worries about Liz but can’t get back to her.

The male survivors meanwhile hope to get a plane up to do some scouting. They don’t succeed in this, but a plane from elsewhere makes a crash landing. It’s a last-ditch effort from a neighboring island, loaded with women and children, and its pilot brings word of a flotilla of male survivors making its way by sea.

Griff and company get together a rescue party on board an LC-3—an amphibious vehicle armed with improvised artillery to fight off sea monsters. On their way they find a stranded Russian sub, which provides opportunity for everybody to stand up for human solidarity against an inimical planet. The big war now is between humans and the natural world, not between human nations. As one of the Americans observes, “I’m inclined to think that the line-up will different from now on—man against fish!”

Proof comes quickly, as one of the missing boats returns. But there’s no way to get to it, with everything in the ocean either deadly or hostile or both—until Liz turns up, emaciated but fierce, with a suggestion. She knows how to make an ointment that repels sea monsters. She rustles up the ingredients (one of which is a wild pig; Griff gets to go on a hunt) and whips up a batch, and off they go to the Island Queen.

The boat is not in good condition. Nearly all its crew is dead, and there’s a monster in the hold: one of the octopus mutants, captured in hopes of studying it. The one surviving crewman, speaking broad island patois, delivers a soliloquy about how “de debbles” of the sea have declared war on the land, and it’s a bad new world out there.

With mighty effort and death-defying adventure, the islanders, Griff, and the Seabees rescue the Island Queen and bring it back to the base, where they imprison its cargo in a pool and persistently fail to communicate with it. Meanwhile they discover that burned remnants of the toxic red algae that has plagued the sea make amazing fertilizer, which means they can plant crops to supplement the Seabees’ huge but not exhaustible stash of supplies. They’re making a go of it, one way and another.

The book ends on an unusually didactic note for a Norton novel. Le Marr and Griff’s Seabee friend Casey have a somewhat lengthy debate about the future of humanity. Le Marr is all about the island life, back to nature, live and let live, and who really knows what “de debble” wants except basically to stay alive? The planet is sick of being abused by humans. It’s time for another species to dominate and for humans to settle down and be quiet. To which Casey counters that you can’t keep human curiosity down. Humans will pull themselves up and start Doing Stuff again.

That’s your kind of human, Le Marr responds. Our kind is more about live and let live. We’re two different kinds, but he allows as how they have to learn to work together, if any of them want to survive.

So basically we’ve got go-getting white Americans and easygoing mixed-race islanders who speak “black English,” and they’re making common cause because they have to, but they’re not really all that compatible. Norton is trying here as so often elsewhere to depict a world that is not all white and not all American, but the dialect and the dichotomy are dated, and goes there with “primitive” and “savagery” as descriptors for the non-whites. Her white Americans are all clean-cut and gung-ho and steely-jawed. And that’s not a universal good thing, but it’s still just a wee bit, as we say around here, of its time.

That time is interesting from the perspective of 2018: twenty-five years after Hiroshima, which puts it at 1970, in a book published in 1957. In that time, atomic engines have been perfected and robots powered by them are building Seabee bases. Sea life has mutated, invasive species are appearing far away from their native habitats, and monsters from the depths have risen to attack humanity. That’s a lot of happenings for a little over a decade, and a remarkably bleak prognosis for human politics.

It’s also a remarkably timely set of themes. Climate change. Ecological disaster. Human depredations on the natural world, poisoning it beyond repair.

To Norton of 1957, the fact that we’re still here and still un-nuked after more than sixty years would be mind-blowing, I think. Not that we’re not in danger of it; right now we’re closer to it than we’ve been in a long time. But we’ve held up better than she feared, politically. Whether the planet is holding up is another question. It’s not radiation that’s killing us now, but carbon emissions.

We’ve learned a lot more about octopus intelligence, too, since the Fifties. The cold, inimical, Lovecraftian cephalopods of Norton’s world have turned out to be bright, curious, ingenious creatures who definitely have their own agenda, but they’re not out to destroy humans. Even the wicked moray eels turn out to make smart and loyal pet-companions, and we’re discovering that sharks can be something other than stone-cold predators. Our whole view of animal intelligence has changed. We’re less into horror now and more into positive communications.

I really enjoyed this one. It’s not, as it turns out, the book I thought I was reading when I reread Star Man’s Son—the noble, wise father I remembered is not the irascible, rather cold-blooded, fairly quickly fridged one here. But it’s a fast, lively read, the setting is remarkably vivid and evocative, and the way the world ends, while somewhat overcomplicated—mutant sea life and the Red Menace and a volcano and nuclear war, all in the same book—definitely makes for some exciting adventure.

Griff is mostly just a pair of eyes for the reader; he doesn’t have much personality. He manages to be right in the middle of all the important stuff, and he’s plucky and courageous and fairly smart. He gets along with everybody, too, which is not a common thing: he fits in wherever he is.

That lets him, and us, be a part of all the human groups that come into the story. He’s young enough to be adaptable and old enough to be aware of how the world is changing. As a viewpoint, he works out pretty well, though other characters, including Liz and Casey and Le Marr and the Seabee commander, make more of an impression.

Next time I’ll be reading the novel that happens to have been bundled with this one in a 2009 Baen edition: Star Gate. I’m not sure how or if they’re connected, but I’ll be interested to see.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published recently by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.